“Database of Global Cultural Evolution

Harvard Faculty of Arts and Sciences

By Bahrami-rad, Duman, Anke Becker, and Joseph Henrich

About

The Database of Global Cultural Evolution links historical data on cultural practices to contemporary populations around the world.

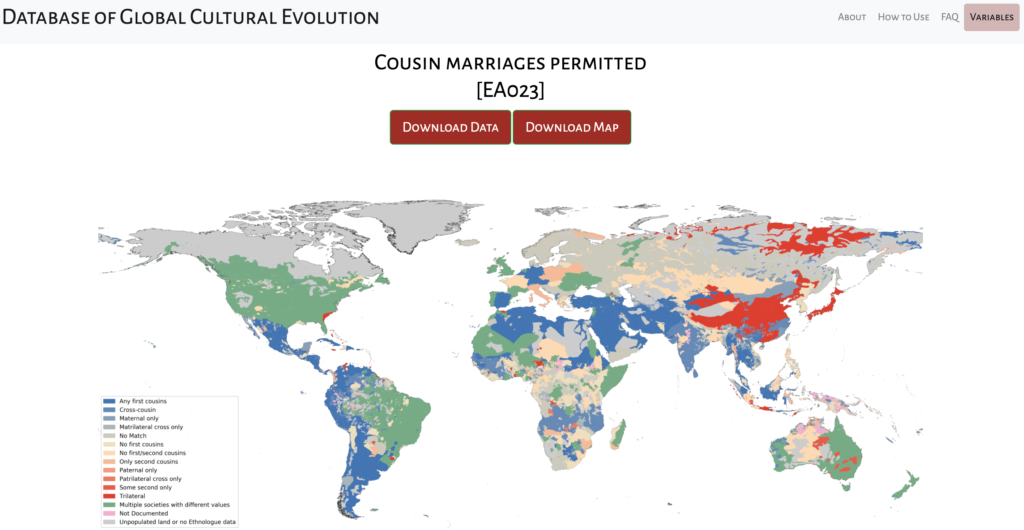

The historical data come from the Ethnographic Atlas (EA), a database containing ethnographic information on 1,291 pre-industrial societies around the world. The Ethnographic Atlas contains coded variables on subsistence economy, social and political organization, marriage and kinship patterns, inheritance, etc.

Contemporary populations in our database are defined based on living languages of the world.

The match between historical data and contemporary populations is based on language. The Ethnographic Atlas includes information on languages of pre-industrial societies. Using this information, we link the pre-industrial data from the Ethnographic Atlas to all contemporary languages using language trees of the Glottolog, a comprehensive catalogue that organizes the world’s languages, language families and dialects via a genealogical classification. To define values of each variable in the EA for all languages spoken by contemporary populations, genealogical trees of the Glottolog are used to match every contemporary language to one of the 1,291 societies from the Ethnographic Atlas. For each variable, every contemporary language is matched to the linguistically closest pre-industrial society which contains an observation for that variable.

Then, geographic information about the global distribution of contemporary languages is used to map the geographic distribution of each variable. Geographic data for living languages come from the Ethnologue, a comprehensive database of world languages.

Finally, the map and data produced for each historical variable (from the Ethnographic Atlas) are displayed for all 7,651 contemporary languages listed in the Ethnologue.

How do I cite the database?

Research that uses the Database of Global Cultural Evolution should cite the following paper:

Bahrami-rad, Duman, Anke Becker, and Joseph Henrich. “Tabulated nonsense? Testing the validity of the Ethnographic Atlas and the persistence of culture.” Working paper.”