Scientism Versus the Theory of Mind – Alex Rosenberg (Department of Philosophy, Duke University)

––––––––––––––––––

Rosenberg, Alex. 2020. “Scientism Versus the Theory of Mind.” Social Epistemology Review and

Reply Collective 9 (10): 48-57.

https://wp.me/p1Bfg0-4Mf

Those who, like me, accept scientism adopt this definition with two elisions easy to spot: we delete the word ‘unwarranted.’ Scientism has obvious and important implications for what an American humorist, Garrison Keeler, called “life’s persistent questions.” Here is a list of some of them, and the answers I believe scientism requires us to give them.

Is there a God? No.

What is the nature of reality? What physics says it is.

What is the purpose of the universe? There is none.

What is the meaning of life? Ditto.

Why am I here? Just dumb luck.

Does prayer work? Of course not.

Is there a soul? Is it immortal? Are you kidding?

Is there free will? Not a chance!

What happens when we die? Everything pretty much goes on as before, except us.

What is the difference between right and wrong, good and bad? There is no moral difference between them.

Why should I be moral? Because it makes you feel better than being immoral.

Is abortion, euthanasia, suicide, paying taxes, foreign aid, or anything else you don’t like forbidden, permissible, or sometimes obligatory? Anything goes.

What is love, and how can I find it? Love is the solution to a strategic interaction problem. Don’t look for it; it will find you when you need it.

Does history have any meaning or purpose? It’s full of sound and fury, but signifies nothing.

Does the human past have any lessons for our future? Fewer and fewer, if it ever had any to begin with (from Rosenberg 2011, 2-3).

(…)

Until Darwin (1859) came along things looked pretty good for Kant’s (2007, XVII) pithy observation that there never would be a Newton for the blade of grass—that physics could not explain living things, human or otherwise, because it couldn’t invoke purpose.

But the process that Darwin discovered—random, or rather blind variation, and natural selection, or rather passive environmental filtration—does all the work of delivering the means/ends economy of biological nature that shouts out ‘purpose’ or ‘design’ at us.

(…)

Hardly anyone accepts scientism. Why not? Distaste? Implausibility? Too hard to understand?

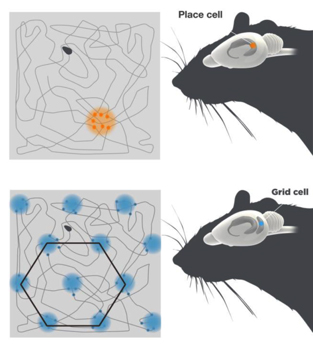

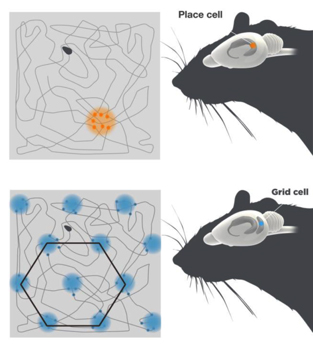

All of the above, but all three of these factors are rooted in the same cause. The rejection of scientism is bred in the bone, as close to hard wired as it can be. It’s caused by our unswerving devotion to the theory of mind, a theory we carry with us and use everywhere and always.

The theory of mind (hereafter TOM) has other names—folk psychology, common sense psychology, the belief/desire model of human action. It has been formalized as the starting point of empirical cognitive social psychology.

(…)

Why does the TOM block acceptance of scientism? To begin with it does so, because it blocks the understanding and acceptance of science. The TOM makes us story-tellers and story-consumers. It’s what makes us love narratives with plots—human motivations fulfilled or thwarted. It’s what facilitates our remembering them, we even use them as devices to remember non-narrative information (cf. techniques for memorizing random lists). The TOM turned humans into hyperactive motivation detectors. Because we can’t escape relying on the TOM, we anthropomorphize everything. But of course, science doesn’t come packaged in stories about good guys, bad guys and their motives, narratives with plots. Science is delivered in laws, equations, models, data-assembles, things we can’t keep in our heads because we can’t assemble them into stories. Our devotion to the TOM obstructs our uptake of science.

(…)

Our reliance on the TOM makes understanding science difficult just because science doesn’t come in stories with plots and motives and stories that we are hard wired to crave, to be satisfied with, to remember. Insofar as science banishes purpose, teleology, design and thus their well-understood causes—desire and belief—from nature, it makes itself hard to accept. More important, the TOM is among the presuppositions of most of our philosophically deep questions, and one of most indispensable building blocks of most of the alternative answers to these questions. Pull the TOM out from under the questions and the answers and they can’t even really be stated or answered in terms we can or will accept. But, as we will see, pulling the rug out from under the TOM is what science does. And that is what makes scientism so hard for people even to understand or contemplate.

(…)

It hardly needs saying that TOM underlies much that scientism rejects just because science makes scientism reject the TOM. Without the TOM, there is no space of reasons in our heads, no place were meanings can lodge and have a role in thought or action. That implies there’s no will, and so no free will, no agency or responsibility, no enduring self that can entertain or respond to reasons, not to mention the interpretations that we overlay on events to give them meaning. Neuroscience banished purpose from our heads as completely as Darwin banished from the rest of the biological domain. Without reasons in our heads, or anywhere else, there are no resources to scientifically construct what Sellars called “the manifest image” required by our culture, civilization, its legal, political, moral, creative, artistic subsystems. The costs of surrendering the TOM are huge, so huge we can’t do it for the practical purposes of everyday life, indeed for civilization as a whole. This fates us to the use of a highly imperfect (predictively unreliable, explanatorily baseless) instrument in the construction and operation of the institutions of our culture. The TOM’s baselessness explains many of their failures, defects and deficiencies.

But all this is too much for science to overthrow. And if creatures like us have a hard time understanding science in the first place, because the TOM that’s bred in our bones obstructs science, then we’ll have an even tougher time even understanding, let alone accepting scientism.”