“Death of the individual. There is no such thing as self, argues professor Tom Oliver”

Neither our bodies nor our minds represent us, claims Prof Tom Oliver

18 JANUARY 2020 • 8:00PM

https://www.telegraph.co.uk/science/2020/01/18/death-individual-no-thing-self-argues-professor/

John Donne, the English cleric and poet, wrote in the 17th century: “No man is an island, entire of itself; every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main”

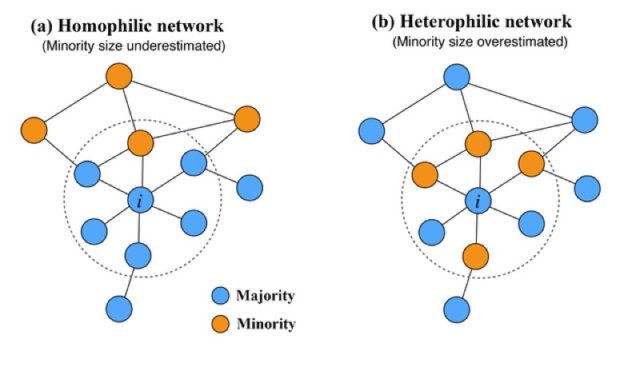

And now a British academic has claimed that human individuality is indeed just an illusion, because societies are far more intertwined at a mental, physical and cultural level than people realise.

In his new book, The Self Delusion, Professor Tom Oliver, a researcher in the Ecology and Evolution group at the University of Reading, argues that there is no such thing as ‘self’ and not even our bodies are truly ‘us’.

Just as Copernicus realised that the Earth is not the centre of the universe, Prof Oliver said society urgently needs a Copernican-like revolution to understand that people are not discrete beings but rather part of one connected identity.

“A significant milestone in the cultural evolution of human minds was the acceptance that the Earth is not the centre of the universe, the so-called Copernican revolution,” he writes.

“However, we have one more big myth to dispel: that we exist as independent selves at the centre of a subjective universe.

“You may feel as if you are a discrete individual acting autonomously in the world; that you have unchanging inner self that persists throughout your lifetime, acting as a central anchor-point with the world changing around you. This is the illusion I seek to tackle. We are seamlessly connected to the world around us.”

Prof Oliver, who is also a government adviser, said his journey as a scientist had led him to believe not only that supernatural powers do not exist, but individual humans do not either.

He argues that there are around 37 trillion cells in the body but most have a lifespan of just a few days or weeks, so the material ‘us’ is constantly changing. In fact, there is no part of your body that has existed for more than 10 years.

And the majority of cells in the body are not human, as we contain more bacterial cells than human cells.

Likewise recent findings in psychology and neuroscience suggest that even our minds are simply an echo-chamber of previously learned beliefs.

“Findings across a wide range of scientific disciplines increasingly support the idea that the central, discrete ‘I’ we obsessively nurture, protect and talk to throughout our lives is just an illusion,” said Prof Oliver.

“Since our bodies are essentially made anew every few weeks, the material in them alone is clearly insufficient to explain the persistent thread of an identity.

“We are like a thread in a tapestry that is unaware of the majesty of the whole interconnected piece. We are not sovereign individuals but part of a deep interconnected universal network.”

Prof Oliver claims that individualism is actually bad for society, and only by realising we are part of a bigger entity can we solve pressing environmental and societal problems.

Through selfish over-consumption we are destroying the natural world and using non-renewable resources at an accelerating rate.

“We are at a critical crossroads as a species where we must rapidly reform our mindsets and behaviour to act in less selfish ways,” he said

“Loosen your grip on the illusion of an independent ‘I’ and open your eyes to the hidden connections all around you.”

The self Delusion: The Surprising Science of How We Are Connected and Why That Matters, W&N are publishing on 23rd January 2020.

***

“The Self Delusion: The Surprising Science of How We Are Connected and Why That Matters (English Edition) eBook Kindle

Tom Oliver

Weidenfeld & Nicolson (23rd January 2020)

https://www.amazon.com.br/Self-Delusion-Surprising-Science-Connected-ebook/dp/B07SZL5H4S

We like to believe that we exist as independent selves at the centre of a subjective universe; that we are discrete individuals acting autonomously in the world with an unchanging inner self that persists throughout our lifetime.

This is an illusion.

On a physical, psychological and cultural level, we are all much more intertwined than we know: we cannot use our bodies to define our independent existence because most of our 37 trillion cells have such a short lifespan that we are essentially made anew every few weeks; the molecules that make up our bodies have already been component parts of countless other organisms, from ancient plants to dinosaurs; we are more than half non-human, in the form of bacteria, fungi and viruses, whose genes influence our moods and even manipulate our behaviour; and we cannot define ourselves by our minds, thoughts and actions, because these mainly originate from other people – the result of memes passing between us, existing before, after and beyond our own lifespans.

Professor of Ecology Tom Oliver makes the compelling argument that although this illusion of individualism has helped us to succeed as a species, tackling the big global challenges ahead now relies on our seeing beyond this mindset and understanding the complex connections between us. THE SELF DELUSION is an explosive, powerful and inspiring book that brings to life the overwhelming evidence contradicting the perception we have of ourselves as independent beings – and why understanding this may well be the key to a better future.